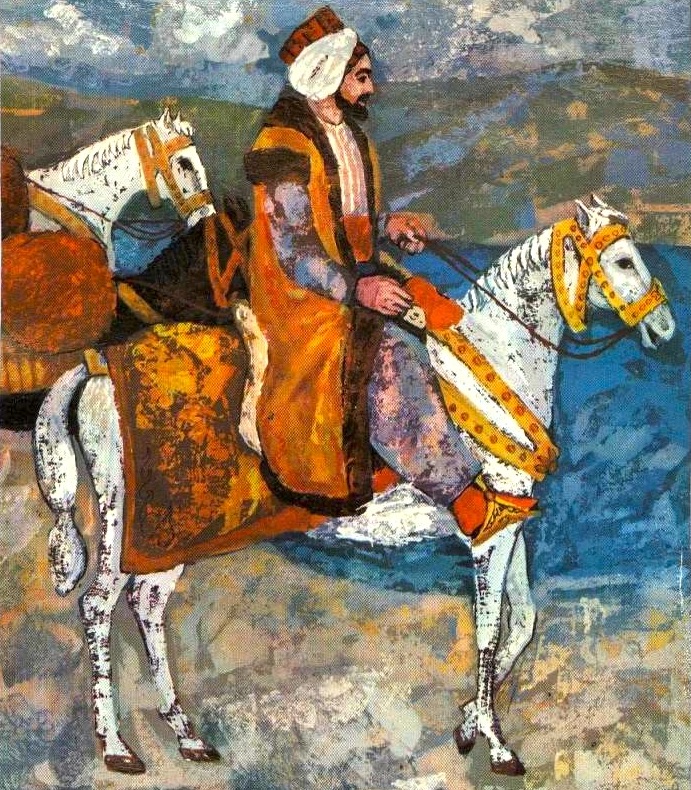

EVLIYA ÇELEBI PAINTING (C) SERMIN CIDDI

According to his own recollection, Evliya Çelebi, the seventeenth-century Turkish writer and traveler, experienced a life-changing epiphany on the night of his twentieth birthday. He was visited in a dream by the Prophet Muhammad, dressed nattily in a yellow woollen shawl and yellow boots, a toothpick stuck into his twelve-band turban. Muhammad announced that Allah had a special plan, one that required Evliya to abandon his prospects at the imperial court, become “a world traveler,” and “compose a marvelous work” based on his adventures.

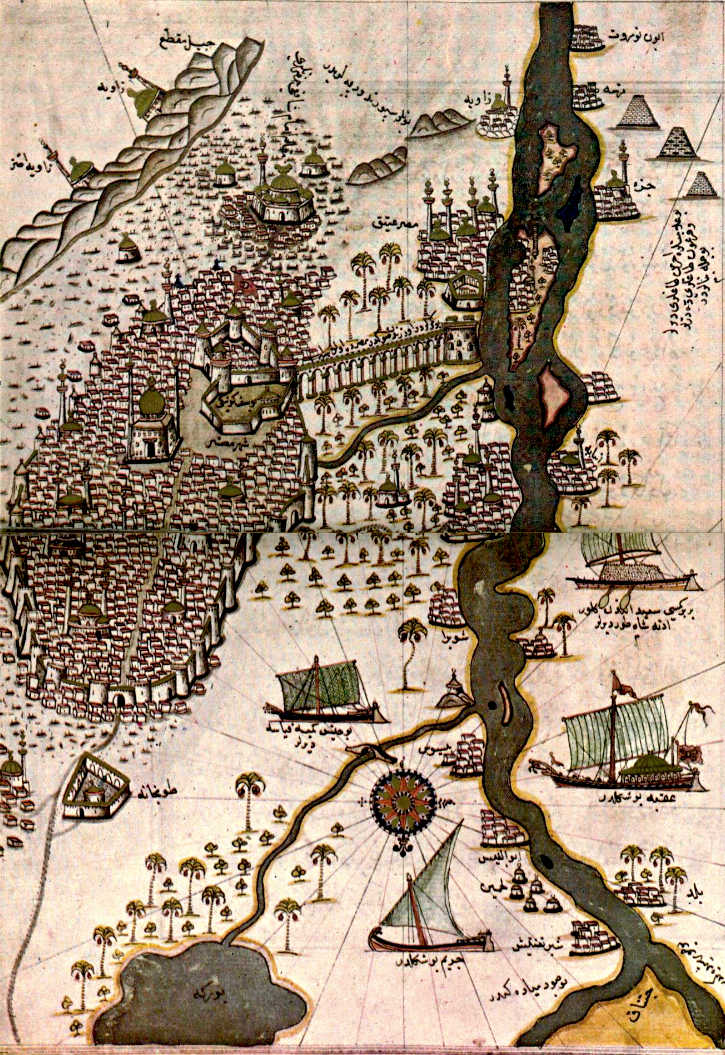

As religious missions go, it was a pretty sweet deal—and for Evliya it came at the perfect moment. His feet itched to travel and his fingers to write, but he could never find a way of telling his parents that the life they had proudly mapped out for him—a stellar career, a virtuous wife, and a brood of smiling children—played no part in his vision of a meaningful existence. Muhammad’s intervention, whether an act of providence or not, spurred three decades of globetrotting indulgence. Evliya took in Anatolia, Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Cairo, Athens, Corinth, Sudan, and swathes of Europe from Crimea to—supposedly—the Low Countries. His path crossed Buddhists and crusading warriors, the Bedouin and Venetian sailors, ambassadors, monks, sorcerers, and snake charmers. Along the way he wrote the Seyahatname (“Book of Travels”), a magnificent ten-volume sprawl of fantasy, biography, and reportage that is utterly unique in the canon of travel literature, and which confirms Evliya as one of the great storytellers of the seventeenth century.

The son of a successful goldsmith, he was born in Istanbul in 1611, the beginning of the end of the Ottoman Empire’s golden age. By the age of twelve, his prodigious intelligence, quick wit, and facility for language had him apprenticed to the imam of Sultan Murad IV; by his early teens he was reciting from memory lengthy passages of the Koran in front of thousands at the Hagia Sofia. Evliya’s Istanbul was cosmopolitan and outward-looking: its population teemed with disparate ethnicities from Asia, eastern Europe, and the Middle East, merchants, scholars, and diplomats from even farther afield, and even a surprising number of Protestant refugees—Huguenots, Anabaptists, Quakers—fleeing war, schism and persecution in Europe.

Evliya so adored the bustling energy of Istanbul that he dedicated the first volume of the Seyahatname to it. In his telling, it was a place of learning, culture, and endless sensory stimulation, where acrobats from Arabia, Persia, Yemen, and India performed in the streets, and where “thousands of old and young lovers” exposed their “rosy pink bodies, like peeled almonds” to the summer sun, swimming and canoodling in the open. That this tribute came from a man who repeatedly described himself as a “dervish”—a man who during the course of his life recited from memory the whole of the Koran more than a thousand times—reveals something vital about his world and his mindset. To Evliya’s mind, the divine and the earthly were bound tightly together; sensual pleasure was not inimical to piety.

Despite his wanderlust, Evliya was actually a pretty lousy traveler: a fussy eater, prone to discomfort, with a fear of boats. And he didn’t travel light, accompanied as he was by mules, camels, libraries of books, and cases of fine clothing, all attended to by at least half a dozen slaves, frequently more. This entourage was itself usually part of the larger retinue of an ambassador on a diplomatic mission or a military leader pursuing territorial expansion, with Evliya tagging along in the role of a glorified jester. Once the jaunt was over he would return to Istanbul to regale the court, including the Sultan himself, with tales of the places he had seen and the scrapes he had gotten into. In this way Evliya reconciled the dual aims of his travels and his writing: to create an objective statistical record of the lands of Allah’s creation, while dispensing with dry fact and serving as a twinkly-eyed “boon companion to humanity.”

As religious missions go, it was a pretty sweet deal—and for Evliya it came at the perfect moment. His feet itched to travel and his fingers to write, but he could never find a way of telling his parents that the life they had proudly mapped out for him—a stellar career, a virtuous wife, and a brood of smiling children—played no part in his vision of a meaningful existence. Muhammad’s intervention, whether an act of providence or not, spurred three decades of globetrotting indulgence. Evliya took in Anatolia, Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, Cairo, Athens, Corinth, Sudan, and swathes of Europe from Crimea to—supposedly—the Low Countries. His path crossed Buddhists and crusading warriors, the Bedouin and Venetian sailors, ambassadors, monks, sorcerers, and snake charmers. Along the way he wrote the Seyahatname (“Book of Travels”), a magnificent ten-volume sprawl of fantasy, biography, and reportage that is utterly unique in the canon of travel literature, and which confirms Evliya as one of the great storytellers of the seventeenth century.

The son of a successful goldsmith, he was born in Istanbul in 1611, the beginning of the end of the Ottoman Empire’s golden age. By the age of twelve, his prodigious intelligence, quick wit, and facility for language had him apprenticed to the imam of Sultan Murad IV; by his early teens he was reciting from memory lengthy passages of the Koran in front of thousands at the Hagia Sofia. Evliya’s Istanbul was cosmopolitan and outward-looking: its population teemed with disparate ethnicities from Asia, eastern Europe, and the Middle East, merchants, scholars, and diplomats from even farther afield, and even a surprising number of Protestant refugees—Huguenots, Anabaptists, Quakers—fleeing war, schism and persecution in Europe.

Evliya so adored the bustling energy of Istanbul that he dedicated the first volume of the Seyahatname to it. In his telling, it was a place of learning, culture, and endless sensory stimulation, where acrobats from Arabia, Persia, Yemen, and India performed in the streets, and where “thousands of old and young lovers” exposed their “rosy pink bodies, like peeled almonds” to the summer sun, swimming and canoodling in the open. That this tribute came from a man who repeatedly described himself as a “dervish”—a man who during the course of his life recited from memory the whole of the Koran more than a thousand times—reveals something vital about his world and his mindset. To Evliya’s mind, the divine and the earthly were bound tightly together; sensual pleasure was not inimical to piety.

Despite his wanderlust, Evliya was actually a pretty lousy traveler: a fussy eater, prone to discomfort, with a fear of boats. And he didn’t travel light, accompanied as he was by mules, camels, libraries of books, and cases of fine clothing, all attended to by at least half a dozen slaves, frequently more. This entourage was itself usually part of the larger retinue of an ambassador on a diplomatic mission or a military leader pursuing territorial expansion, with Evliya tagging along in the role of a glorified jester. Once the jaunt was over he would return to Istanbul to regale the court, including the Sultan himself, with tales of the places he had seen and the scrapes he had gotten into. In this way Evliya reconciled the dual aims of his travels and his writing: to create an objective statistical record of the lands of Allah’s creation, while dispensing with dry fact and serving as a twinkly-eyed “boon companion to humanity.”

Evliya’s written legacy is the Seyahatname, or Book of Travels, comprising 10 volumes and thousands of pages composed in the highly recondite language of Ottoman Turkish. To date, only parts of it have been translated into English, by Robert Dankoff and Sooyong Kim, from whose book the quotations in this article are taken. As the translators note, their job was not easy, for Evliya’s language is prolix, exuberant and playful, full of allusions to the Qur’an, folk proverbs in Arabic and Turkish, and classics such as Firdawsi’s Shahnama and Sa'di’s Gulistan.

And, as things often went in the Ottoman Empire, it was due to the good offices of an unusual palace insider—in this case, Hajı Beşir Ağa, the Chief Black Eunuch—that Evliya’s manuscript was plucked from obscurity in a Cairo library decades after his death and brought to Istanbul in 1742, where it was copied and widely read.

And, as things often went in the Ottoman Empire, it was due to the good offices of an unusual palace insider—in this case, Hajı Beşir Ağa, the Chief Black Eunuch—that Evliya’s manuscript was plucked from obscurity in a Cairo library decades after his death and brought to Istanbul in 1742, where it was copied and widely read.

He settled in Cairo where he died in 1684, one year after the Ottomans’ infamous failed siege of Vienna, traditionally put down as the beginning of the end of the Ottoman Empire. By this point the Seyahatname was thousands of pages long and years away from being finished. It had been written to be read, but it was only half a century later that a eunuch at the Ottoman Palace brought the huge, tattered manuscript back to Istanbul in order to be copied. Without that, the name Evliya Çelebi would mean nothing to anyone; the Seyahatname is practically the only evidence of its author’s existence.

Today, in his native Turkey, Evliya is revered as the quintessential expression of the Ottoman mind: inquisitive, outward looking, and presciently modern. In 2014 he inspired the nation’s first ever feature-length 3D animated film, a kids’ movie, Evliya Çelebi: The Fountain of Youth, sponsored by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism seemingly to help frame Turkey as unique among nations, a land simultaneously of both East and West. In the movie he winds up in modern-day Istanbul; a seventeenth-century Ottoman imperialist comfortable in the democratic Turkey of the twenty-first century, Evliya is intended to embody a spirit of Turkish openness, one that links Istanbul’s Ottoman past with the hip, Euro-friendly image it likes—on occasion—to project today.

The Turkish ministry has it wrong in one crucial respect: Evliya was not the Turk in excelsis, but a man without precedent who stood one step aside from his countrymen, a singular man of singular achievement. The type of life he wanted to live and the type of stories he wanted to write could not be accommodated in a conventional travel journal, or any other type of writing familiar to the Ottomans, so he created one. As Evliya himself stressed, “Evliya Çelebi is a wandering dervish and a world traveler … wherever he rests his head, he eats and drinks and is merry.” As often as not, that place was the endless horizon of his own glittering imagination.

Today, in his native Turkey, Evliya is revered as the quintessential expression of the Ottoman mind: inquisitive, outward looking, and presciently modern. In 2014 he inspired the nation’s first ever feature-length 3D animated film, a kids’ movie, Evliya Çelebi: The Fountain of Youth, sponsored by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism seemingly to help frame Turkey as unique among nations, a land simultaneously of both East and West. In the movie he winds up in modern-day Istanbul; a seventeenth-century Ottoman imperialist comfortable in the democratic Turkey of the twenty-first century, Evliya is intended to embody a spirit of Turkish openness, one that links Istanbul’s Ottoman past with the hip, Euro-friendly image it likes—on occasion—to project today.

The Turkish ministry has it wrong in one crucial respect: Evliya was not the Turk in excelsis, but a man without precedent who stood one step aside from his countrymen, a singular man of singular achievement. The type of life he wanted to live and the type of stories he wanted to write could not be accommodated in a conventional travel journal, or any other type of writing familiar to the Ottomans, so he created one. As Evliya himself stressed, “Evliya Çelebi is a wandering dervish and a world traveler … wherever he rests his head, he eats and drinks and is merry.” As often as not, that place was the endless horizon of his own glittering imagination.

Above information taken from: www.theparisreview.org/blog/2016/08/05/boon-companion/